The beginning of the year is a great time to reflect on the previous year’s goals and to start planning for the next year’s annual plan. An annual plan is a document that lists goals, strategies, action items, deadlines, and metrics for success.

As a college administrator, I regularly create goals and strategies for my academic division, and I also work together with a team of leaders and managers to create goals for other areas of the college. I enjoy doing this work because strategic thinking, planning, and goal-setting are natural skills for me. I have also had a lot of training in leadership, strategy, management, and goal-setting from my MBA degree.

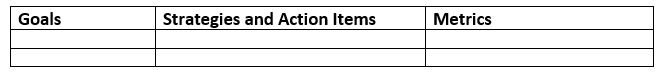

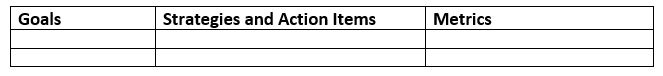

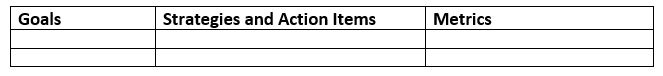

In this blog post, I will describe the process of strategic annual planning for an academic division. The process usually requires that you write goals, strategies, and metrics on a spreadsheet with three columns.

Are Goals Given or Created?

Colleges have top-level institutional goals that are set by the Board of Trustees and executive administrators. These goals are very public – they are posted on the college’s website, and the college president talks about them at Board Meetings and during all-staff meetings.

These goals are of two types:

- Specific action items focused on one area of the college, such as “Increase Enrollment” or “Expand Student Housing.”

- Broader, college-wide goals, such as “Promote Academic Excellence” or “Improve student and faculty support services.”

The first type of goals – the specific action items – often pertain to a specific area of the college. For example, “Expand Student Housing” may be a specific project for Facilities or Fundraising but not for Academic Affairs or Student Services. In these cases, the institutional goal gets handed down (or assigned) to a specific division. The manager or director of that division simply has to copy and paste the goal into the annual plan.

For example, during the Covid pandemic, my college transitioned to fully online/remote learning, and technology support services became a major priority (a top-level goal) for the college. This institutional goal was assigned to the Dept. of Academic Technology. The department didn’t have to create a new goal; it copied the existing goal from the college’s Strategic Plan, and it added the goal into the department’s annual plan. Instead of creating a new goal, the department had only to find ways to execute the goal.

In contrast, broader goals apply to several areas of the college. For example, the goal to “Promote Academic Excellence” can be the responsibility every academic program, the Tutoring Center, the Library, the technology department, the Office of Accreditation and Academic Assessment, and the Center for Teaching & Learning. In this case, each of these departments will need to include this goal in their annual plan, and they’ll need to find unique and specific ways to support it.

Often, the annual plan will have a mix of goals that your division is directly responsible for (the top-level goal is assigned directly to you), goals that you contribute to or support, and goals that pertain only to your department.

How to Create Goals

For goals that are assigned to your department, simply copy them as they are. These goals can be found in the college’s Strategic Plan or in the annual plan for higher-level divisions, such as the VP’s or Dean’s office.

Goals you support or contribute to are also pretty much copied (but maybe not exactly) from other higher-level departments. For example, if a broad goal in Academic Affairs is to “Promote Academic Excellence,” you could copy that exact phrase, or you could make it a little more specific: “Promote academic excellence by hosting faculty development workshops.” When you connect your goal to a broader goal at the college, you often have to identify which broad goal you are supporting. Often, goals are numbered, so after your department’s goal to “Promote academic excellence,” you may put (AA#3) to show that your goal is connected to Goal #3 in the annual plan for Academic Affairs.

You can also create goals that pertain specifically to your department. Often, these goals reflect a project your department (or a department that reports to you) would like to complete or one that will help them improve. There are several things to consider when creating these goals:

The goal should reflect a value or a need within the college. The goal can promote one of the college values or loosely contribute to one of the top-level goals. For example, “fiscal responsibility” may be assigned specifically to the Business Office, but a Student Services department may want to evaluate their spending as well.

The goal should promote a unique and specific value of that department. The value or need may not be shared across the college, but it may be important for that specific department. For example, the Technology Help Desk may have a goal to “be more responsive and timely” by responding to every ticket within the same day. Or, the Business Department may have a goal to “Promote Innovation.”

The goal should push you, rather than be routine. The goal should be related to the work of the department, but it should not be a routine task. For example, the goal of the Advising Center should not be simply to “Help Students Register for Classes.” It does that anyway. Instead, the goal should push the department to do something a little extra. For example, the Advising Center may improve the registration process by “Implementing New Online Course Registration Software.”

Goals for One-Time Projects. Some goals are going to be one-time activities. For example, implementation of new software or hiring a new staff member or updating a course syllabus are going to be a one-time thing.

Goals for Recurring Processes. Recurring goals measure a routine process, and they should have some kind of direction or momentum. Avoid process goals such as “Help students enroll.” Instead, create a target the department can work towards, such as “Increase the number of enrollments before the end of the semester.” This goal can be performed each semester, and it will help the department increase the number. In order to do so, it would need to improve its operations and communications with students. Each semester the goal is to improve.

Goals Based on Job Duties. Goals should be related to the work your staff can do; they should fit within their job description, not be something completely different. For example, a Librarian should probably not have to participate in direct fundraising even if the college needs to raise funds for an upgrade to the Library. Direct fundraising (“schmoozing” with donors) may push the Librarian beyond the scope of their job duties. But, they can help in other ways, such as by researching strategies for fundraising or by organizing a book sale.

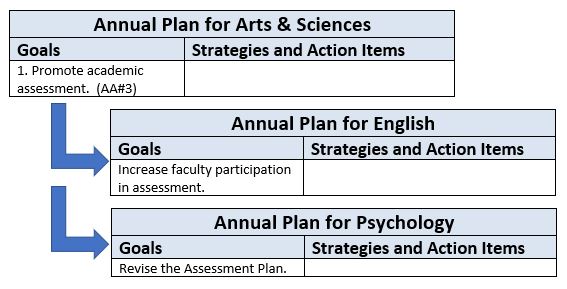

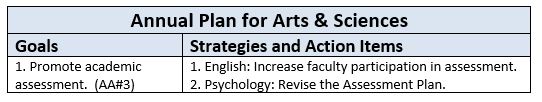

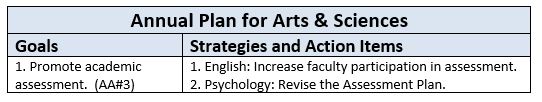

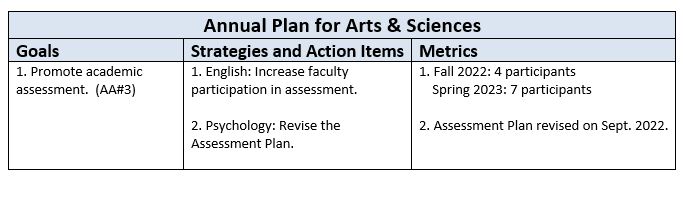

Broad Goals in the Division or Department. If you lead a large division with several department units, the annual plan could have a broad goal that applies to the whole division. Then, each department can create their own specific goals that support that division goal. For example, the Arts & Sciences division may have a broad goal to “Promote Academic Assessment.” Then, specific goals can be assigned to each academic department within the division. For example, the English Dept. may need to “Increase faculty participation in assessment,” while the Psychology Dept. may need to “Revise the Assessment Plan,” and the Math Dept. may need to “Improve student understanding of linear equations.”

One approach is to have an annual plan for the division and separate annual plans for each academic department.

Another approach is to have an annual plan for the division and to list goals for each department as a strategy.

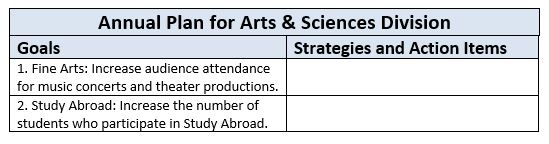

Collection of Specific Goals. If you lead a large division, the division’s annual plan can have a collection of specific goals for each department, instead of a broad goal that is shared by all departments. For example, at my college, many academic departments don’t write an annual plan; instead, the division’s annual plan has a collection of goals from several departments. For example, the annual plan may have a goal for the Fine Arts Dept. that says “Increase audience attendance for music concerts and theater productions.” On the same annual plan, there may also be a goal for Study Abroad that says “Increase the number of students who participate in Study Abroad.” In this way, the annual plan for the division serves as a collection of specific goals for each department unit.

In real practice, the annual plan is going to have a mix of several types of goals. You’ll also have to decide how many goals the annual plan will have. This will depend on how many departments report to you and whether the annual plan has broad goals for the whole division or a collection of specific goals for each department.

My annual plans usually have one or two higher-level goals that are assigned to my division, two to four broad goals for the division (such as “promote assessment” and “provide opportunities for professional development”), and at least one specific goal for each department, plus I also include goals that are specific to my own unique responsibilities as the division leader.

SMART Goals: Clearly Define the Goals

When you create goals, you’ll probably have to go through a brainstorming process (ideally in collaboration with your managers and staff) where you list many possible goals and some kind of evaluation/selection process where you decide which goals to keep and which ones to eliminate. This process will likely involve listing all goals, revising them, getting feedback from others, evaluating if goals are achievable and relevant and timely, ranking the goals, and selecting which goals you’ll keep.

As you list, evaluate, and select goals, you’ll have to ensure they are effective. A very well-known strategy for creating effective goals is the “SMART” acronym, which helps ensure that goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Timely. The SMART acronym will help you write and select goals that can realistically be accomplished.

Specific – The goal should identify a specific outcome or action, rather than a generic hope. For example, “Improve Student Understanding of Linear Algebra” is more specific than “Increase Student Achievement,” and “Revise all Psychology Syllabi” is more specific than “Promote Academic Excellence.” As you create a goal, ensure that it is specific enough so staff know what they are asked to do.

Measurable – The goal should be “observable” (something you can see), and there should be levels or indicators you can track. This tracking will help you evaluate your progress. For example, “Increase Student Assessment Results in Oral Communication from 2 to 3” is more measurable that the general statement of “Improve Student Achievement.” You can use a specific rubric to evaluate student speeches, and you can assign a number, but it’s difficult to track a general sense of “achievement.” Use specific “indicators,” such as a score on a grading rubric, exam, assignment, or survey when you create a goal.

Achievable – Goals should be challenging and inspiring, but they should not be so lofty that they can’t be achieved. Goals that are too challenging may intimidate and discourage your team. Set a goal that is just beyond the team’s current level of performance, or set a goal to start with, then increase it later on. “Increase Final Exam Scores from 75% to 78%” is much more realistic than “Increase Scores from 75% to 85%.”

Relevant. Relevant means that the goal is “related to” or “appropriate for” the department or the college. As discussed above, goals should be related to the college’s mission and values, to goals of higher-level departments, to the function of the department, and to the job duties of employees in the department.

Time-Bound. The goal should have a specific time window for achievement. Strategic Plans for the college often last 4-5 years, and some goals such as promoting student success and academic quality are always on the strategic plan. But lower-level departments often write annual plans each year, so the goal should ideally be completed within one year, one semester, or a shorter amount of time. Nevertheless, recurring/process goals could stay on the annual plan for several years so the department can evaluate results on a longitudinal basis (over many years).

Timely. The goal should also be appropriate for the current situation. Renovating the science lab or building new student housing would not be appropriate if the college is experiencing financial hardship. Similarly, writing the college’s assurance argument for accreditation would not be timely/appropriate if the deadline is 3-5 years away. Even if these goals align with college values and are important to the department, they won’t happen if there are other projects that are more urgently needed at this time.

From Goals to Action Steps and Strategies

A strategy is an action that accomplishes a goal. Educational goals are typically complex and require the work of several people or several departments over a sustained period of time; as a result, the goal is going to have several action steps. Or, a goal may be accomplished in different ways; as a result, it’s going to require several strategies. An effective annual plan will identify these specific action steps and approaches in the “Strategies” column.

Here are several examples for the Strategies column.

Division to Department. If the annual plan lists a broad goal for the division, each department could have a different strategy. For example, the English Dept. could “promote assessment” by getting more instructors involved in the process, while the Psychology Dept. could update its assessment plan, meanwhile the Math Dept. could try to increase its assessment results. In this case, the column for “Strategies” would identify a strategy for each department.

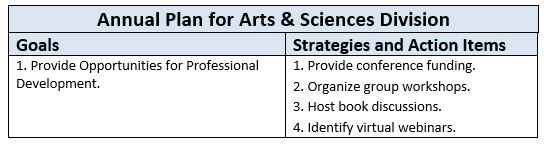

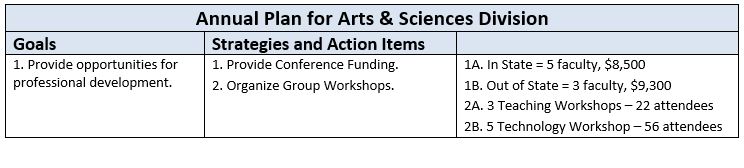

Many Different Strategies. Broad goals could be accomplished in many different ways, or a department may try more than one way to accomplish the goal. For example, strategies to “Provide Opportunities for Professional Development” may include conference funding, group workshops, book discussions, and virtual webinars. These could all be done simultaneously or at different times of the year, and they can be performed by the same team rather than by a different department.

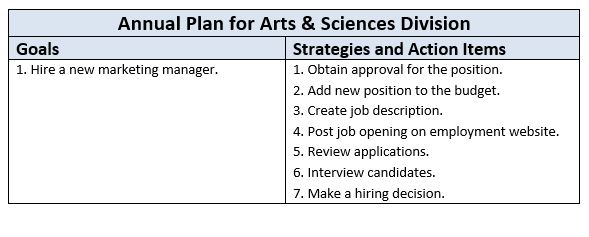

Several Specific Action Steps. Some goals have a clear sequence of action steps. For example, the process for hiring a new employee includes getting approval for a new position, budgeting for it, creating a job description, posting the job opening, reviewing applications, interviewing candidates, making a hiring decision, and negotiating a salary. Each action is separate, and there is a sequence of action steps. For goals like this, the “Strategy” or “Action Step” would be to identify the steps, put them in order, and create a schedule. When all action steps are complete, the goal will be accomplished.

The number of action steps will depend on the complexity of the goal. Some goals can be accomplished all at once, while others have many components. The number of strategies for each goal will also depend on the number of departments/teams working on the goal, the ability of the team to implement more than one approach, and the nature of the goal itself. Goals for marketing, student recruiting, and academic support can be approached through many strategies, but goals for accreditation and budgeting may have fewer approaches.

Identify Metrics and Ways to Track Progress

As you implement goals, action items, and strategies, you’ll need to identify ways to track your progress. These are called “Measures,” “Indicators,” “Targets,” “Accomplishments,” or “Metrics,” and they are listed on the right side of the table.

Metrics can take many forms.

Binary. Some goals and strategies can be accomplished easily, and without much explanation. As a result, you may need only to indicate that the goal or strategy was “accomplished”/”Yes” or “Not Accomplished”/”No.” For example, if an action was to “Obtain Approval,” the metric could indicate whether approval was obtained or not. Or, if the strategy to promote academic quality was to update course syllabi, the metric could indicate that “Syllabi were updated.”

Record a Date. For binary metrics, I like to add a date: “Syllabi were updated in Fall 2022.” Dates can also be useful for strategies related to events and action items. For example, if the strategy is to organize a group workshop, the metric could indicate all the dates a workshop was hosted: “Workshops hosted on Sept. 1, Sept. 15, Sept. 30.”

Numbers, Measures, Counts. Accomplishments often measure numerical values, such as amount of money, number of attendees, student enrollments, how many times an activity was performed, how many items were completed, and so on. In these cases, the metric will indicate the measure. For example, “250 Biology Majors,” “27 attendees at the workshop,” “62 of 87 assessment reports completed.”

Any Other Qualitative Result. For some goals, the outcome may be more qualitative than numerical. In this case, you may need to write a narrative or an explanation of what happened or what were the results. For example, the result of an accreditation report may be: “Program accreditation extended for two years, but accreditors gave significant feedback that will need to be addressed.” Outcomes like this could lead to new goals.

Single or Multiple Indicators. As you identify outcomes and metrics, consider whether the strategy has one or multiple indicators.

- Single-Indicator: Success for strategies with a single indicator can be determined by looking at only one outcome. For example, there is only one indicator for “Increased Enrollments” (number of students who enroll) or “Increase Revenue” (amount of money earned). This is the only number that needs to be tracked.

- Multiple-Indicator: In contrast, complex strategies have many components that could be tracked. In this case, you will either need to decide which (one, most-important) indicator of success you will track, or you will need to track all indicators. For example, in the goal to “Provide Opportunities for Professional Development” and the strategy to “Provide Conference Funding,” you may need to track the dollar amount, the number of attendees, and the type of conference. And for the strategy to “Organize Group Workshops,” you may need to track the type workshop and also the number of attendees.

Indicators are important for helping you demonstrate that the goal, strategy, and action item was actually achieved. The indicator can also inspire a new goal for the following year.

Summary

The beginning of the new year can provide a great opportunity for reflection and planning for your department’s annual strategic plan. The plan is often written on a spreadsheet or a table with three columns that include the Goal, the Strategies and Action Items, and the Indicators of Success.

Do you need help with your annual plan? Contact Lirim for consulting services.

Lirim Neziroski, Ph.D., MBA is a higher education administrator, education consultant, and previous faculty member with expertise in higher education leadership, instructional technology, curriculum development, academic assessment, and leadership of academic and online programs. Contact Lirim for consulting, research, writing, and public speaking opportunities.

Leave a comment