I am writing a series of blog posts about the effects of Covid-19 on higher education. In this post, I explore the effects of Covid-19 on academic assessment, both on student assessment within individual courses and on program assessment for academic programs. This article is based on a presentation I delivered at the Illinois Community College Assessment Fair in February 2021.

Student assessments include any graded assignments, exams, projects, discussions, or other activities that evaluate student learning. In many cases, major assignments within a course are used to generate data about student learning for program-level assessment reports, program reviews, and accreditation documents.

During the pandemic, many academic programs transitioned to an online, remote, virtual, or hybrid format. In this transition, student assessments were some of the most difficult components to move to the online environment. Academic programs had to create online versions of these assessments, or they had to find new online assessments they could use as substitutes.

Assessment Processes

Academic programs evaluate student learning on many levels.

- For an Individual Unit or Assignment. At the lowest level, assessments such as chapter quizzes evaluate student understanding of course content, such as terminology and concepts described in the chapter, information for a particular unit in an anatomy course (nervous system, muscular system, skeletal system, etc), a clinical skill such as blood pressure and pulse taking, and so on. These assessments cover one or more days of course content, they evaluate a few specific learning outcomes, and they account for a fraction of the grade in the course.

- For a Course. Many courses have a major end-of-semester project, writing assignment, final exam, portfolio, or other activity that encompasses the whole semester’s worth of content knowledge. This assessment measures student understanding and ability in several categories or learning outcomes, and the assessment counts worth a large part of the course grade. For example, in one course I helped develop online, the Final Exam accounted for 50% of the course, while everything else accounted for the other 50%. In many courses, it is common for the final exam or final research paper to count worth 20% or 30% of the course grade, and graduate courses may base the whole course grade on a single end-of-semester project.

- Major or Degree. These assignments – and other requirements (such as number of courses, clinical experiences, internships, volunteer hours, capstone projects, etc) – also contribute towards the student’s evaluation for a degree.

- Academic Program. These assignments, plus institutional surveys, retention and graduation information, alumni and employer feedback, and many other sources of information are used to evaluate the quality or success of the academic program. Assessments like writing projects, final exams, and licensing exams are used as evidence for the success (or challenge) of the academic program; when students are doing well, the academic program is successful; when students struggle, the academic program may need some changes. Academic programs are evaluated in several ways; the most common are program assessment reports (which evaluate the quality of student learning at the program level), program reviews (a holistic review of the academic program that includes a review of enrollments, graduation, revenue, expenses, staffing, resources, quality of curriculum, and more), and an accreditation report (similar to a program review, but it goes to an external accrediting agency).

Each academic program identifies assessments it will analyze before writing program assessments, program reviews, and accreditation reports in a document called an Assessment Plan. The Assessment Plan often includes the title of the assessment, a description, an explanation of how and when it will be administered, and an expected outcome or target.

Covid Disruption

Many academic programs have assessment processes for collecting data, analyzing it, and making decisions. But the transition to online because of the Covid pandemic in Spring 2020 disrupted these processes. All of a sudden, many established assessment practices disappeared, and academic programs had to find replacement assessments or risk going without data.

Academic programs that already had online assessments were already in a position to use their online data sets. But programs that were administering in-person assessments had to quickly adopt alternative online assessments. Some of these programs already had online course sections, so they simply expanded the online assessments into all course sections. But many programs had to invent much more innovative ways to assess students and their program outcomes.

From Blue Books to Respondus

It’s almost unbelievable to instructional technology people like me that academic programs in 2019 and 2020 were still using in-person, paper-based multiple-choice exams and even Blue Books for in-class essays. But many academic programs did so, and they had some good reasons.

- Programs could hold a simultaneous, multi-section exam period to discourage cheating without having to combine online course sections in the LMS.

- Many schools don’t have a computer lab big enough to do administer computer-based exams for large or multiple course sections, so they use paper instead.

- Not all students have a laptop to bring to class. And, even if they did, the classroom may have unreliable wifi and not enough power outlets.

- Even computer-based exams require some kind of Browser Lockdown or multiple exam proctors to discourage cheating.

- Some courses (particularly in Math and Science) preferred paper exams because it is easier for students to draw symbols, formulas, and chemical bonds on paper, plus the paper exam allows students to show their work and intermediate calculations.

Nevertheless, many of these programs did transition from in-person, paper exams to online exams. Many instructors wrote or uploaded exam questions to their LMS, downloaded question banks from publisher platforms such as Pearson or McGraw-Hill or Elsevier, or they setup course sites on publisher platforms such as Elsevier and had students take exams there. All of these transitions involved a few hurdles.

- Instructors needed help importing exam questions. Luckily there are templates for importing questions in bulk through CSV and Word files, so instructors and instructional technology staff were able to help move this content quickly without having to type each question.

- Some programs needed additional LMS packages to allow video-based exam questions or questions with math and science symbols. Without these packages, some instructors simply uploaded images into questions and answer choices, and this did not meet accessibility standards (because the images could not be translated by screen readers, and there was no alternative text description for the image).

- Some instructors created downloadable homework assignments instead of exams. Students could download or print a Word or PDF file, then submit their work by uploading the document, scanning it, or even uploading pictures from their cell phone. This approach eliminated exam security, but it allowed students show their work. Uploading the completed assignment-quiz was also a challenge; students didn’t have scanners, they had trouble uploading unrecognized image types, or they uploaded several blurry images.

- The online exams also needed exam security. A few academic programs were using external platforms such as the HESI for Nursing or MyMathLab or MyAccounting Lab for online exams, but the school suddenly needed an exam platform for all students. Many schools partnered with exam security platforms such as Respondus or Proctorio. These platforms required additional, unplanned funding (though the CARES Act helped cover the expense), and students and instructors needed training and technical support for the new technology.

- Some of these exam security platforms required webcams, which students didn’t have, so colleges had to quickly buy and distribute external webcams or laptops with built-in webcams. On a few occasions, students took exams on their old computer or laptop, and they used a video conferencing platform such as Zoom or Google Meet or Microsoft Teams on a cell phone for live video proctoring with an instructor.

Writing Assignments

Many in-person courses were already collecting student work through the LMS. But those that were not quickly started to collect assignments through the LMS (and sometimes via email). The assignment collection was simple – it needed only an online submission page.

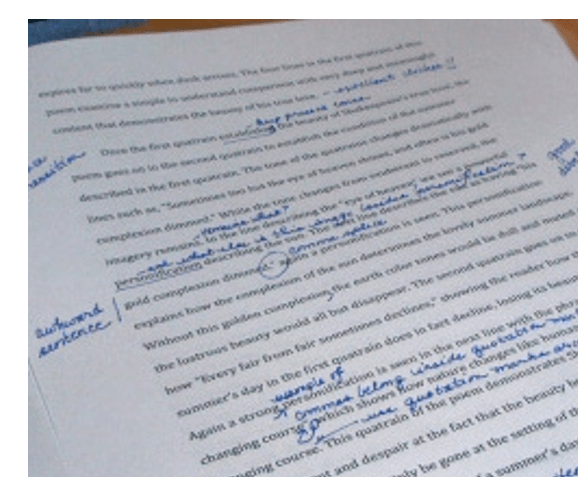

The grading was a little more challenging. Many instructors enjoy writing on the paper document itself; they write comments in the margin, circle punctuation and grammar errors, draw arrows, and do many other things. This tactile approach to grading is not so easy to replicate online. Online options include:

- Using document commenting tools on the LMS.

- Downloading the document and using commenting tools in another computer program, such as a PDF reader, Google Docs, or Microsoft Word. Some PDF readers allow instructors to make drawings on the document, if they have a touchscreen computer or a tablet.

- Opening the document in another online grading platform such as the Turnitin Feedback Studio.

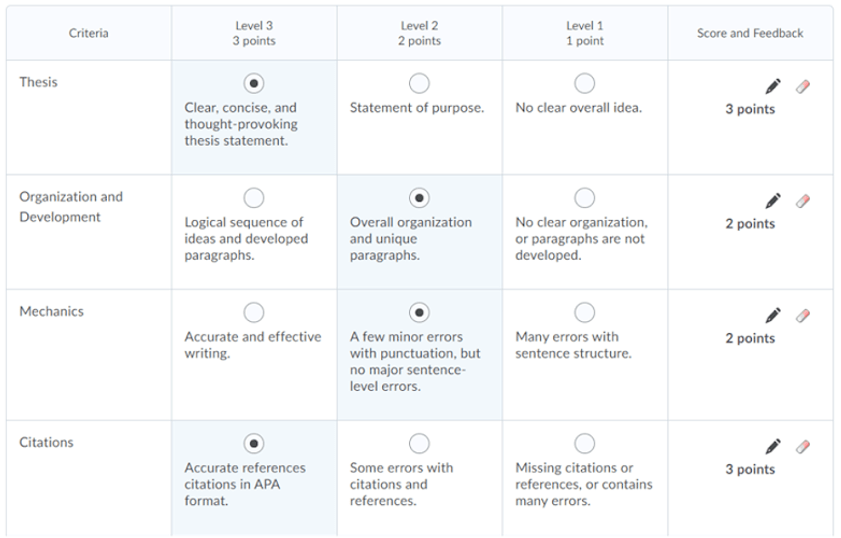

Many courses also use grading rubrics. When grading on paper, a paper rubric can be filled out by hand and stapled to the assignment document. When courses transitioned online, instructors and instructional designers created online versions of the assignment rubric. Instructors could grade online assignments by clicking the appropriate box on the rubric, and they could also add comments and adjust the score.

In my view, rubrics are a faster, more efficient, and more meaningful way of grading assignments. Effective rubrics contain grading categories (such as thesis, evidence, citations, and grammar), and they provide explanations about each level, so students can clearly see how the assignment is evaluated and what’s the difference between a Level 3 and a Level 4 score. Plus, typed comments on rubrics are easier to read than an instructor’s handwriting, arrows, and circles, and components of the rubric can be linked to online resources such as a grammar section or a citation website.

Assignments that depended on group work and other in-person activities were the most challenging. In these cases, students used video conferencing platforms and shared documents through Google Docs, Microsoft SharePoint, or other platform to collaborate. And online assignments could be setup as group assignments with a single submission.

Discussions

Discussions are normally an important component of online courses. Discussions allow students to ask questions about course content, apply course concepts, experiment with ideas on low-stakes assignments, provide and receive feedback from other students, develop a classroom atmosphere, share resources with classmates, and learn from diverse student perspectives.

When in-person courses transitioned to the online environment, they could replicate live class discussions through video conferencing platforms and virtual break-out rooms, or they could engage in asynchronous discussion throughout the week. In these environments, discussion could be graded by participation, by the number of posts and responses, and by an evaluation rubric.

Labs, Clinicals, Studios, and Other Experiential Learning

Many assessment types described above could be moved to the online platform pretty easily: paper exams became online exams, written assignments became online LMS submissions, in-person discussions became virtual break-out sessions.

But courses with experiential learning components, such as science labs, art studios, Nursing clinical courses, welding, auto mechanics, culinary programs, and more could not transition to the online environment so easily. In many of these courses, students perform hands-on activities, and assessments evaluate their physical abilities, skills, and performances. Many of these programs adjusted to the new way through the following strategies:

Limited In-Person Labs. Some courses continued to use the lab but with fewer students, with social distancing, with masks, with more cleanings, and with many other safety precautions. The fewer number of students, though, meant that the lab had to stay open for longer periods of time, students had to go to the lab outside their regular class time, instructors and lab proctors were putting in more time in the lab, use of cleaning supplies and funding (already precious commodities) were increasing or unavailable. Some institutions, though, shut down completely, so this limited in-person approach was not possible.

At-Home Lab Kits. Some experiential learning activities could be replicated at home. For example, students in art courses did not have to be in an art studio to make their artworks. Students in basic science courses could observe differences between physical states of matter at home (ie, freeze water, melt it, boil it), or they could do simple measurements with a bathroom scale, cooking or refrigerator thermometer, and rulers at home. Some science experiments even have lab kits that could be purchased and conducted at home. At-home lab kits, though, are very limited; experiments often require students to use chemicals and expensive scientific equipment they do not have at home.

Online Assignments. Some courses transformed their in-person clinical or lab assignments into online or virtual assignments. For example, instead of giving speeches in class, students recorded their speech with a cell phone or webcam, and they uploaded it to the LMS. Students in Nursing clinical courses also recorded videos of clinical skills such as hand-washing and blood pressure checks conducted on family members. These assignments allow instructors to observe physical performances – such as body language, hand gestures, and volume during a speech – so they could assign a score for those components, plus these videos could be uploaded to a discussion board for peer feedback. But, invasive clinical skills that can be performed only in a classroom setting cannot be replicated at home, and the instructor’s feedback is not as immediate and interactive as would be in a clinical skills lab.

Virtual Assignments. Some of the immediacy of a clinical evaluation could be replicated through a live video conference. For example, a student could demonstrate a blood pressure check via Zoom or Microsoft Teams, and the instructor could provide guidance in the moment. But, again, the procedures are limited because of equipment and privacy. The session may also be limited by the quality of the video or camera. For example, it may be possible for a student in a music studio course to play the piano or clarinet at home via video conference, but the quality of sound may not be captured by the cell phone or computer webcam, and the instructor is limited to mostly verbal feedback.

Instructor Involvement. In some science classes, the student was not able to conduct the lab experiment, but the instructor or lab proctor was. Students described the lab experiment in writing, instructors set it up according to the student’s description, they performed the experiment to completion, they collected results and sent them to students, and students were able to analyze the results, draw conclusions, and write the rest of the lab report. The experiential component of the science lab was definitely transformed – the lab became a writing project – but students were still able to meet course learning goals (such as analyze data and write a lab report), and the academic program still had some student assessments it could evaluate for program-level assessments and program reviews.

From Service and Experiential Learning to Problem-Based Writing Assignment. Many upper-level courses include experiential learning components, such as field research, service-learning, and other applied learning activities, where students conduct research, design a project, implement the project, and write a reflection essay or report based on their experience. During the pandemic, students did the research, and they designed the project, but they were not able to implement their projects, so they couldn’t learn from experience. Instead, they could only reflect on their research and problem-solving.

Video Databases and Simulation Activities. When many experiential forms of learning became unavailable, academic programs turned to video databases and online simulations. In Surgical Technology courses, for example, students watched video surgeries instead of participating in a surgery, and they wrote about the patients, instruments, and procedures in the video instead of about their own experiences. Students in Dental Assisting and Dental Hygiene courses completed online exams with “hot spots” that allowed them to select the correct area of a tooth virtually instead of demonstrating it on lab equipment. Nursing students also watched videos and completed interactive online activities instead of participating in live clinical sessions.

Conclusion

Many of these assignments transformed the experiential learning activity into an online activity or written assignment, but these strategies allowed students to complete many assignments and to demonstrate their skills and knowledge. These assignments also provided student assessment data for future assessment reports and program reviews.

The transition to online was not always easy, and for some programs the continuing online, virtual, or remote approach to learning is still problematic, but programs that were able to find alternative online assessments were able to evaluate student learning and collect data for program assessments.

Lirim Neziroski, Ph.D., MBA is a higher education administrator, education consultant, and previous faculty member with expertise in higher ed leadership, instructional technology, curriculum development, academic assessment, program leadership, and strategic planning. Contact Lirim for speaking, consulting, and writing opportunities.

Leave a comment