I am writing a series of blog posts about the effects of Covid-19 on higher education. In this post, I explore the effects of Covid-19 on college finances. Many academic institutions were already struggling financially; they had to make major cuts, lay off staff, and pull money from endowments because of their financial situation. I know the pain of this personally. As an administrator, I have been part of budget committees where I had to cut and cut and cut major items from my budget each month. Finally, I was the one who was cut – I have been part of layoffs at two institutions.

For many institutions, Covid-19 has meant lower retention, lower enrollment, less revenue, and more expenses. These pressures have put a lot of stress on colleges that were already struggling financially. At the same time, we also hear about colleges that are setting new records in fundraising and also receiving millions of dollars in CARES Act funding.

Pre-Covid

Many schools were struggling financially even before Covid. Leading experts have been claiming for years that higher education is on the verge of a major collapse.

One of the most famous examples of this doomsday prediction was by Harvard Business School Professor Clayton Christensen, who predicted in 2017 that 50% of U.S. colleges could go bankrupt in 10-15 years. Subsequent articles in Forbes and elsewhere have followed with similar predictions that “Half of All Colleges Will Close” or merge or be bought out if they do not make major changes.

These predictions have come true in some instances. In Illinois, where I live, this interactive map on Higher Ed Dive shows that MacMurray College, Robert Morris University, Chicago ORT Technical Institute, and Morthland College have closed or merged since 2016. Inside Higher Ed also has a list of 20 private, non-profit colleges that have closed since 2016.

Many other colleges that have not closed have been running deficits for years (their expenses are higher than their revenue), have pulled money out of endowments, and have made drastic cuts to staff, faculty, academic programs, student services, and operations. In short, even though these colleges are not closed, they are limping along, and they may be on the path to closure.

Why the Financial Struggle?

There are many complex reasons for the financial struggle, and most struggling institutions probably have several causes that are working against them simultaneously. Here are some common causes:

- Too Much Debt. Like all businesses, colleges have to take on debt to expand and invest in the future. Colleges use this borrowed money to build new dorms, athletic facilities, science labs, cafeterias, computer labs, renovate the library and classrooms, etc. And, just like any other mortgage or long-term loan, this debt comes with monthly payments, and these payments eat away revenue for years and years. Many colleges are now paying expensive loans they took out in the past. At that time, they believed that the future would be better, but the investment has not always paid off, and the lower enrollments have made it difficult for colleges to cover other necessary expenses.

- A better approach may have been to use donations or grant funding to pay for these projects, but donations and grants can take a long time to collect, and they may come with requirements. Luckily, schools may be able to refinance the loan for a lower interest rate or setup a balloon loan, but the monthly payment is going to be high nevertheless because projects like new buildings often cost millions of dollars.

- Too Many Expensive Services and Obligations. Many colleges have increased spending year over year because they keep launching new services, such as academic technology platforms, online tutoring, simulation centers, campus security, and much more. Also, existing services such as employee salaries and healthcare costs, library subscriptions, technology expenses, conference and travel fees have also increased year over year, which means that colleges are also spending more money for the same services.

- Declining Revenue from Enrollment and Student Housing. At the same time as services are getting more expensive, many colleges have been losing enrollments (for a variety of reasons – fewer college-age students in the area, more online alternatives, high cost of college attendance), and this means colleges are losing revenue from both student tuition and also from student housing (dorms).

- More Scholarships (Discounts). In an effort to attract more students, colleges have also been giving discounts in the form of scholarships (academic, athletic, assistantships or fellowships, work-study, etc.), which means that colleges are collecting less revenue even from the students they are enrolling. In recent years, many colleges have averaged a 48% “discount rate,” which means that the college is collecting about 52% of the tuition. Colleges have also faced many financial aid reimbursement issues, which means they are not receiving tuition payments from external sources. For example, in Illinois, the state government has not always paid its MAP funding on time, or it has not paid for several semesters. In this example of MAP payments Illinois did not make in 2015-16, the U. of Illinois was out about $30 million each semester; other state universities were out $3-10 million. This means that these universities had to cover daily operations from existing funds, without getting reimbursed the $72 million the state owed in 2015-16.

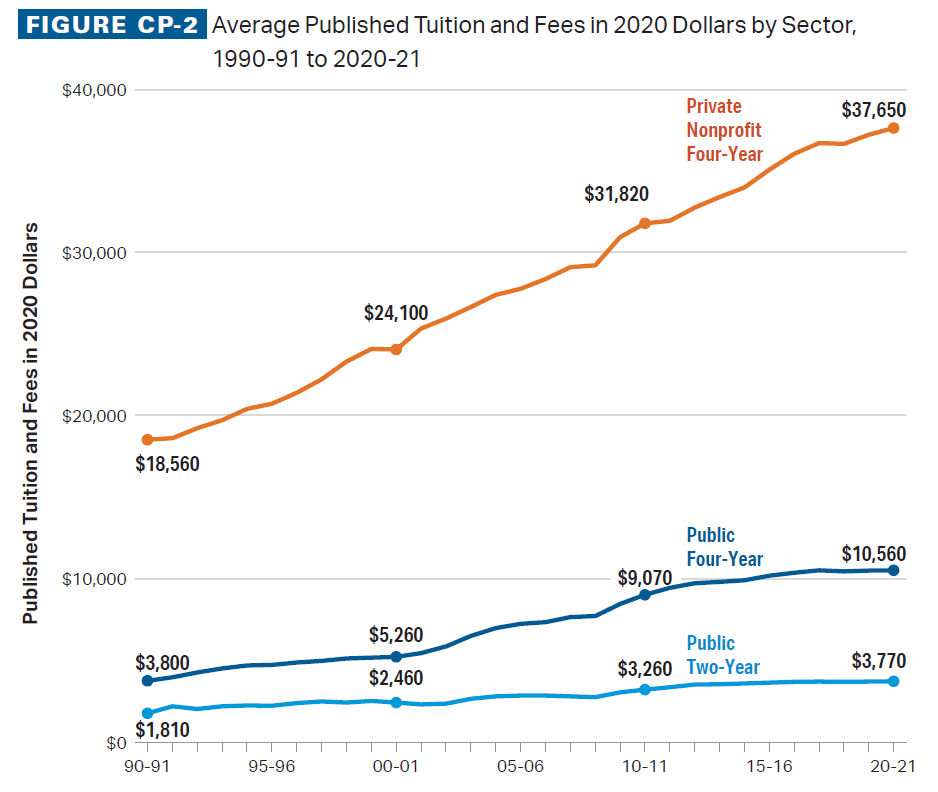

- Cheaper Tuition. Believe it or not, even though there is a financial aid crisis, many colleges have also reduced tuition or kept it “frozen” for several years, particularly for online and graduate programs so they can compete with large online universities that have very low prices. A tuition increase in a time of pandemic also “looks bad,” so many schools (particularly community colleges) have kept their tuition at the same price. Plus, schools that serve disadvantaged communities have a mission not to create additional barriers to access, so they keep tuition as low as possible and are fundamentally opposed to tuition increases. (See tuition data from the College Board.)

Many of these causes are reasonable when considered individually. For example, if students want better dorms, you have to take on more debt (or launch a big fundraising campaign) to build new buildings. Or, if competing schools are decreasing tuition, how can you keep higher prices?

But many schools have also made bad, late, or ineffective decisions and investments that have not worked out. In these instances, colleges may have entered into expensive long-term agreements, overpaid for services and materials, missed opportunities for growth and investment, or expanded programs in the wrong area, or relied too heavily on expense-producing services.

Covid Problems

In many instances, Covid-19 made things worse. All of a sudden, colleges lost revenue from athletics, conferences, dinning services, student housing, parking, and more. Some colleges even had to return money to students who had already paid for dorms. They also had to spend more money on cleaning services and online technology. All of a sudden, every instructor needed a laptop for home, plus a video conferencing platform such as Zoom, and a webcam.

According to this Chronicle article, the higher ed industry lost 650 thousand jobs due to Covid.

“At no point since the Labor Department began keeping industry tallies, in the late 1950s, have colleges and universities ever shed so many employees at such an incredible rate.” (Chronicle)

Many of these cuts probably came from departments that could not transition to an online or virtual format, such as athletics, maintenance, and student activities. In some schools, cuts have affected academic programs as well, as colleges have cut whole academic divisions or offered buyouts, early retirements, furloughs, and other cuts to employee benefits. According to Higher Ed Dive, U. Vermont is planning to cut 27 academic programs in Arts & Sciences, 150 employees took a buyout offer at U. Kansas, Arizona cut 250 employees, Delaware laid off 120, and Rutgers cut 1,000 employees.

Additionally, many states experienced a financial decline in 2020 (and possibly in 2021) due to Covid, and this will mean that some states will have budget trouble at the state level. As a result, states may not be able to provide sufficient funding for academic institutions. For example, California schools are anticipating a decrease of $1.35 billion from the state’s original allocation, and the Chronicle reports an anticipated 14% decline in state support throughout the U.S.

Overall, the Chronicle projects a loss of $183 billion for higher education – $85 billion in lost revenue, $24 billion due to Covid expenses, and a $75 billion decrease in state funding.

Meanwhile, employees whose jobs were not cut are also working under different conditions. Science labs and Nursing clinical and simulation labs, for example, were closed for much of 2020, and graduate research labs have been operating with less funding or have shut down completely as they deal with Covid restrictions or shift to new priorities.

Some Positives

But the financial news is not all bad. Elite colleges are still able to raise large sums through fundraising, and their multi-billion-dollar endowments continue to rise as the stock market sets new records just about every week.

Nearly every school has also received federal funds through the CARES Act, and there is more to come under the Biden Administration. Colleges have used to this money to promote safety measures (such as more cleaning, masks for employees, separators in offices, and even grants to upgrade the ventilation system). The money has also helped colleges transition to online, virtual, and remote learning by helping them purchase technology such as laptops, webcams, and virtual simulation eLearning packages. (Search how much CARES Act funding each school has received.)

The Biden Administration has also promised more funding for community colleges, state schools, and HBCUs in the form of free college tuition and greater funding for research. (See more information from my previous blog post.)

Other good news comes from job predictions in career fields such as data analytics which could increase enrollment in graduate programs.

Overall, there is a lot of support for higher education, but government support cannot make up the losses the industry has experienced.

Lirim Neziroski, Ph.D., MBA is a higher education administrator, education consultant, and previous faculty member with expertise in higher ed leadership, instructional technology, curriculum development, academic assessment, program leadership, and strategic planning. Contact Lirim for speaking, consulting, and writing opportunities.

Leave a comment